The Sum of the Parts or the Whole of the Parts? Part 1

Some thoughts on the microfoundations delusion

The Structure

“Mathematics, rightly viewed, possesses not only truth, but supreme beauty—a beauty cold and austere, like that of sculpture, without appeal to any part of our weaker nature, without the gorgeous trappings of painting or music, yet sublimely pure, and capable of a stern perfection such as only the greatest art can show.”

- Bertrand Russell

One would hardly disagree with the above statement. You can almost sense what mathematics meant for someone like Russell who was at the forefront of the field in the early 20th century. The words were personal in a factual sense too, since he, along with A N Whitehead, wrote the Principia Mathematica in which they attempted to base or reduce the entirety of mathematical knowledge to a set of concrete, precise, and universal axioms (the infamous “mathematicians who took 300 pages to prove 1+1=2”, yaa it’s them). Russell saw himself as a sculptor, sculpting or creating a structure from the ground up, in the way probably even defining what the ultimate ground or base is for the structure, and then slowly but surely refining it till it lacked any imperfections, till it was cold and ruthless, but perfect.

If you have been paying attention to the italicized words, there is a common thread that links them, mainly that we are talking about building or constructing an imaginary structure from the ground up, since logically and practically that is the only way, with a base that’s firm enough to support the structure. We rarely think about the fact that when we speak of scientific progress or advancement in our collective knowledge, we are unconsciously thinking in terms of a structure that grows tall as we progress, in fact when we say that we stand on the shoulders of giants such as Newton or Euler, there is an implicit thought of building up this “edifice” of knowledge.

There is a cruel irony in all this. On the one hand, it is baffling how we all operate in this (and not to get too metaphysical) collective mind-space that derives from reality but is also not real in the physical sense. For example, our mathematical concepts don’t have real physical counterparts in nature, and yet we can use them perfectly to describe not only physical reality in which an engineer or physicist would be interested but also an economic and social reality which has no tangible counterpart, as in definitions and concepts which are derived from reality but are our constructions, such as GDP or the unemployment rate. These imaginary constructions allow us immense flexibility to impact our tangible realities in the form of advanced technologies and a better understanding of human nature. We can simultaneously build these structures while also refining and sometimes changing the very foundations of our knowledge, such as in the case of Newton (Gravity), Einstein (Relativity), and Cantor (Set Theory).

On the other hand, we are so attached to the physical sense of a building that we forget that the imaginary structure that we are building need not adhere to the physical laws of nature, in our case that would mean that one has to build a structure from the ground up, with solid foundations. We put all our efforts into explaining reality from the bottom up, starting from the very beginning itself, in the hopes that we would build up enough to grasp our complicated world, but we forget that this road is a dark one with probably no end in sight, something which the founders of this vision, the mathematicians, realized a century ago when Godel threatened the entire edifice of ever having immutable foundations.

But this post isn’t about Godel’s challenge (He is btw the guy walking beside Einstein in the movie Oppenheimer at Princeton, a person so smart that Einstein looked forward to the conversations he would have with him daily, and also a neurotic jew before Woody Allen made it his thing). It is about how the “micro-foundations” delusion crept into economics and put it on a path that would comfort even string theorists in thinking that they are on the right track!

The Metaphors

First, we have to deal with the role of metaphors in economic thinking.

In his book, The Microfoundations Delusion1, J.E King starts with the role of metaphors in economic arguments. Actually, before we head there, let me clarify in the simplest of terms what micro-foundations in economics mean. As the word suggests, It’s the process of deriving the behavior of the aggregates from the behavior of the individual. It’s the belief that what happens in the aggregate is just a magnified version of a micro reality, and because we mostly can only observe macro aggregates due to computational and time constraints, it has to be the case that the macro represents a single individual, in an economy that assumes that all individuals are almost alike in order to not create greater difficulties. This is indeed a clever trick since it allows the field to treat an entire goddamn economy as a single, absolutely rational agent who is maximizing his objective with respect to some constraints in accordance with perfect mathematically derivable laws about the way it will behave. Turns out that it’s a clever metaphor at best, and wrong in its entirety.

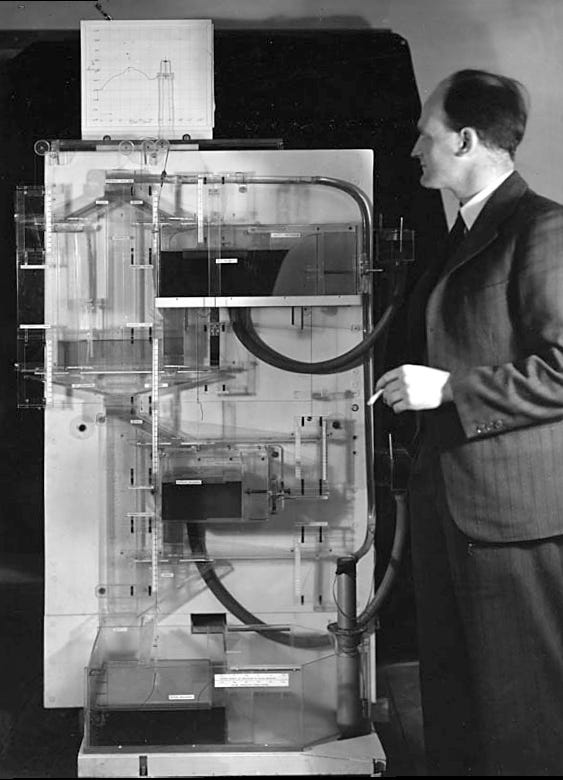

King cites the importance of Deirdre Mccloskey in understanding how economic arguments are not merely logically sound models but rhetorics. In her classic book, The Rhetoric of Economics2, Mccloskey stresses that most philosophical arguments are rhetorical devices that are intended to persuade audiences of their respective arguments. When a macroeconomics professor talks about the circular flow of an economy, he or she, without perhaps realizing it themselves, is attempting to persuade you to conceptualize the economic system as a hydraulic system with the liquids being money and physical goods, with its leakages and injections in the form of savings and investments respectively.

This is not to say that all arguments are ultimately persuasions in some grand post-modernist conspiracy way, but rather that almost all knowledge proceeds ahead by the use of analogies that can be taken from some other source, and in this metaphors are not mere literary devices but rather terms that affect the way in which people go ahead with their theories. Once you start thinking about the way we engage in discussions about economics, metaphors seem hard to miss as they have become so entrenched. In another classic book, More Heat Than Light3, Philip Mirowski dissects how 19th-century economics took concepts straight from physics and applied them verbatim in economic analysis: Human beings as individual particles, the economic system as an engine that tended to get “overheated” etc. It has been the other way around too, as is well known that Darwin was strongly influenced by Malthus’s work on population growth and scarcity, concepts that form the basis of Darwinian evolution and survival of the fittest. The point is that these analogies and metaphors remain long after they have been proposed as they get assimilated within the core explanations and theories of a field, and a successful metaphor is a dead metaphor since it’s used so routinely that no one questions its origin anymore.

Now that we have seen that almost all knowledge endeavors progress ahead with the use of analogical and metaphorical thinking, are all metaphors equally good in guiding us toward building better models of reality?

Not really, says King, and micro-foundations is one of those bad ones. According to Scott Gordon, there are four steps that an analogy is supposed to cross before it is deemed worthy of being used to explain phenomena:

The proposition (P) and analogy (A) need to have a high degree of similarity yet also differences so that they are not exactly superimposable

(A) needs to be explicable on its own

(A) needs to be true, otherwise, the use of the analogy to explain (P) is useless

The causal mechanisms need to parallel each other for both (A) and (P)

According to King, if P is the statement “Macroeconomics require strong micro-foundations” and A is the statement “All Buildings require strong foundations”, then the second and third point stand, but not the other two; the differences between the statements are not trivial, and the causal mechanism need not mimic each other. In essence, it is possible to study the evolution of aggregates without it being based on micro-foundations. This does not mean that macro theory should have no connection to micro reality as King stresses multiple times, the only key point is that the former need not necessarily be built up from the latter, rather they can exist side by side without compromising on economic modeling.

A case in point would be Keynes’s General Theory4. The revolutionary consumption function is based on a strong behavioral assumption about how an individual allocates his current income between savings and consumption, which is micro in nature, yet statistically on an aggregate level too it translates well, thereby not requiring how each individual chooses to allocate his income. Kalecki further improves upon this by having different aggregate consumption propensities for different social classes which incorporates more realistic elements of an economy. But perhaps the most famous example that stares microfoundations on its face is the paradox of thrift, a case of fallacy of composition; It states that an increase in individual savings would lead to lower total savings due to total output/income reducing in an economy. Another case is that of hoarding deposits in times of economic uncertainty, which might provide temporary relief to individuals but worsens the macroeconomic situation, leading to bank runs and eventually lower incomes for all. These examples betray intuition since they don’t follow the additive nature we come to expect with aggregates, and are much more about the relationships between different units that cause fluctuations at the macro level.

We are now on the brink of some important philosophical problems. First, as King points out, micro-foundations also violate the principle of downward causation, i.e. events at the macro level affecting an individual’s micro-decisions or outcomes. This opens the doors to the fundamental dichotomy of reductionism and holism within epistemology, a debate that spans fields from theoretical physics to neuroscience and much more. Second, we need to take “emergence” and complexity seriously, to begin grasping how large structures or systems emerge out of countless micro-interactions that cannot in any logical way just be “added” up to get a macro picture.

In the next post, we will dive further into the reductionist/atomist/Newtonian/Hicks dogma, contrasting it with the holism/emergent/Einsteintian/Keynes reality.

King, J. E. (2012). The microfoundations delusion: metaphor and dogma in the history of macroeconomics. Edward Elgar Publishing.

McCloskey, D. N. (1983). The rhetoric of economics. Journal of economic literature, 21(2), 481-517.

Mirowski, P. (1991). More heat than light: economics as social physics, physics as nature's economics. Cambridge University Press.

The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, 1936.

Absolutely loved this! Honestly, I have heard a lot of buzzwords when reading up about this, but never seen anyone explain this so clearly!